What is leadership? This is a question many have tried to answer, offering various definitions. John Maxwell, perhaps one of the best-known popular authors on the subject, famously summarized it as influence: “Leadership is influence, nothing more, nothing less.” Others emphasize that for leadership to be effective, relationships are essential (Kouzes & Posner); others emphasize certain traits (Thomas Carlyle); while still others analyze effectiveness through various lenses, such as transformational leadership (Burns), servant leadership (Greenleaf), or adaptive leadership (Heifetz). Still others delve into the various components of leadership skills and competencies, seeking to understand how one can become an effective leader (Stephen Covey). Everything from great man traits to various leadership theories seeks to dissect the secret of its effectiveness.

I contend that while there are many definitions, traits, explanations, and theories that all contribute to what we recognize as leadership, leadership, in essence, is very simple. Leadership is choosing to act. At its heart, it is the willingness to move in a particular direction to accomplish something. This definition is so simple as to be obvious and perhaps unworthy of study. However, it is the simple, obvious things that are easily overlooked, which make for the most powerful principles. And that’s the point. Leadership is nothing without action. For leadership to take place, no matter the environment, one must first choose to act. One decision, however small, can set off a chain of influence far beyond what we imagine.

Therefore, at its heart, leadership requires movement. Without action, leadership remains abstract, a mere concept rather than a lived reality. James put it this way: “Be doers of the word, and not hearers only, deceiving yourselves” (James 1:22). Leadership in ministry is not merely about knowing, teaching, or planning; it is about stepping out in faith and acting in obedience to God’s call. Learning the truth of the gospel is useless without acting on it (James 2:19). Leadership in ministry must reflect this principle. Things such as influence, relationships, and vision matter only if they are translated into faithful, God-directed action. Again, the foundation for all leadership rests on this simple principle: leadership is choosing to act.

The Power of Small Acts

While that definition may seem too simple, many seemingly simple things can serve as powerful principles, leading to significant, often unexpected outcomes. For example, consider what some call the Butterfly Effect. Rooted in chaos theory, it suggests that a small change in a system’s initial conditions can lead to massive, unpredictable consequences over time. It highlights that even seemingly insignificant actions can have far-reaching ramifications. A classic example is the idea that a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil could, theoretically, influence the weather in Texas weeks later. This illustrates how small acts that are easily overlooked can have profound and far-reaching consequences. Also, consider the Domino Effect. This theory describes a chain reaction in which one event triggers a series of similar, interconnected events. For example, making your bed in the morning can set off a domino effect of productivity, leading to a sense of accomplishment and motivating you to complete larger tasks. Making one’s bed is such a simple, easily overlooked task that very few people might consider that doing that one thing in the morning can change the trajectory of one’s life. Or think of Lao Tzu’s famous saying, “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” This proverb emphasizes that even the most daunting tasks or long journeys can be accomplished by taking a small initial step. To accomplish something, you must take the first step in the direction you want to go. What otherwise might look like a daunting journey becomes a series of interconnected actions that culminate in a desired end.

Other examples abound. Think about the effect of compounding. This is usually applied to money. This principle, famously called the “eighth wonder of the world,” emphasizes that consistent small efforts, especially when applied to investing, can lead to exponential growth over time. According to Charles Schwab, interest earned on an investment also earns interest, ballooning one’s initial investment. The principle also extends beyond finance to other areas of life, like skill development through consistent practice or the cumulative effect of small, healthy lifestyle changes. Small changes in one’s diet and exercise can have a positive impact on a person for life. Or how about the idea of active listening? This is more than just hearing words; it involves fully engaging with the speaker, paying attention to their nonverbal cues, and responding in ways that demonstrate understanding and empathy. This simple act can build trust, validate the speaker, foster stronger relationships, and even facilitate problem-solving. It promotes effective communication by allowing you to better understand the speaker’s perspective, influencing understanding, and all you have to do is pay attention and listen when someone is speaking. Then there is the often-overlooked act of gratitude. Expressing appreciation for what one has is a powerful practice that boosts happiness, improves physical and psychological health, and strengthens relationships. Studies have shown that consciously practicing gratitude can reduce negative emotions like resentment and envy, improve sleep, strengthen the immune system, and foster mental resilience. Even small acts of gratitude, like thinking of someone you’re grateful for as you wake up or sending a thank-you note, can have a significant positive impact on your well-being and relationships. It’s the simple things that make the biggest impact.

Biblical and Theological Foundations

More examples could be offered, but they all share the same trait. They are simple things that have profound effects. Leadership is no different. It begins when one chooses to act. Something as simple as exercising that principle can change the world. We see this same principle at work in Scripture. When Moses obeyed God’s call and returned to Egypt, it seemed like an impossible task. It was one man against the mightiest empire of the time. Yet leadership began the moment he chose to act, returning to Egypt in obedience to God’s command. That simple act of obedience set into motion the deliverance of Israel (Exod. 3-14), and ultimately it ushered in the Messiah who earned salvation for the entire world (John 3:16). When Nehemiah heard of Jerusalem’s broken walls, he could have remained in the comfort of Persia. Instead, he acted, and his decision sparked a movement to rebuild God’s city. He rallied the people to take action: “Come, let us rebuild the wall of Jerusalem, and we will no longer be in disgrace” (Neh. 2:17). Similarly, Peter’s decision to step out of the boat (Matt. 14:29) demonstrates that leadership is not about perfect confidence but about acting in faith. The pattern is clear: small actions taken in faith lead to great outcomes.

Jesus’ parable of the mustard seed (Matt. 13:31–32) reminds us that the smallest seed can grow into the largest tree. In the same way, the smallest act of faithful leadership, when empowered by God, can bless multitudes. For church and ministry leaders, this means we cannot wait for perfect conditions, unlimited resources, or unanimous approval. God calls us to step forward in faith, trusting Him with the results. The choice to act, however simple, is where leadership is born.

Theologically, this principle reflects the character of God Himself. The God of Scripture is not passive; He is a God who acts. Creation begins with divine initiative: “And God said, ‘Let there be….” and it was so (Gen. 1). Redemption unfolds in history because God “so loved the world that He gave His only Son” (John 3:16). To lead, then, is to image the God who acts. Leaders reflect His nature when they step forward in obedience, even when the path is uncertain.

Theoretical Foundations

While Scripture provides the ultimate foundation for leadership, engaging leadership theory enriches our understanding of how action operates within leadership practice. Several frameworks highlight that leadership is not passive but inherently active, requiring leaders to move, decide, and initiate.

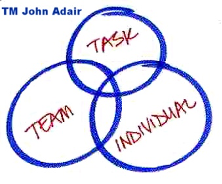

John Adair’s (1973) Action-Centered Leadership argued that effective leadership involves balancing three interdependent areas: Task, Team, and Individual.

- Task: Leaders must act to define and accomplish objectives.

- Team: Leaders must act to build cohesion, trust, and collaboration.

- Individual: Leaders must act to meet the needs of followers, supporting and developing them.

Each area represents a leadership function. Leaders must serve the needs of the individual, the team, and the goals the team seeks to achieve. It is important to see that each function overlaps with the others. As a leader meets one need, it will influence the other two needs as well. For example, building a strong team will help it accomplish its tasks. Meeting individual needs will free up the team members to participate in teamwork. And meeting an objective or goal will give the team a reason to celebrate together.

Let’s consider each leadership function:

Task needs: the team has specific tasks to accomplish. The leader’s function is to provide the team with clarity and a sense of purpose regarding those goals and tasks. This includes communicating expectations, planning to achieve goals, organizing to ensure goals are achieved, and managing team members throughout the process.

Team needs: a leader must be intentional about building and maintaining the team. Leaders effectively build teams when they give the team a shared sense of purpose and empower team members to take responsibility/ownership for meeting that purpose. Good leadership builds teams that effectively work together. This is achieved by fostering a shared culture in which standards are upheld and excellence is celebrated. The most effective tool the leader has for this task is communication. As the team is shaped, the leader not only communicates effectively but also creates a culture where open communication between team members is the norm.

Individual needs: the leader develops the team’s people. While the team has a holistic function, each person brings much to the table. Each person must be valued for what they contribute, and the leader should be intentional about training, providing opportunities for growth, and offering opportunities to take on challenging work. Further, the leader should ensure good working conditions and recognize and validate work well done. This will help individuals to gain confidence in their work.

Adair’s model reinforces the central point of this chapter: leadership exists only when leaders choose to act across these domains. A leader who refuses to make decisions, to move forward, or to engage with people is not truly leading. The triangle of task–team–individual reminds us that leadership action is holistic, requiring simultaneous movement on multiple fronts.

Kurt Lewin et al (1939) early work on leadership styles (autocratic, democratic, and laissez-faire) also emphasizes the necessity of leader action. While styles differ in the degree of control or collaboration, each involves active choices by leaders that shape group behavior. Leaders who abdicate action (laissez-faire) often create dysfunction; those who engage (whether autocratically or democratically) decisively influence outcomes. This further demonstrates that, without action, leadership does not occur.

Specifically, this study found that autocratic leadership led to aggressive behavior and apathetic submission. While productivity was initially higher under autocratic leadership, it dropped significantly when the leader left the room. Groups showed more submission to the leader and a greater need for instructions. More hostility was observed, especially when the leader was absent, suggesting that “tension” created by the leader needed an outlet through hostility. The democratic leadership style led to greater creativity and innovation, and to a collaborative, inclusive culture that fostered open communication and teamwork, resulting in stronger relationships and improved morale. Productivity was slightly lower than in autocratic leadership when the leader was present, but it declined very little in the leader’s absence, suggesting greater group autonomy and intrinsic motivation. The laissez-faire leadership model demonstrated the lowest productivity and could lead to confusion and poor coordination. It was considered so ineffective for group functioning that it was abandoned in future studies.

James MacGregor Burns (1979) and later Bernard Bass (1985) described transformational leaders as those who act to inspire followers through vision, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Transformational leadership is inherently dynamic, requiring leaders to step forward, take risks, and embody change. This complements the biblical truth that faithful leadership moves from conviction to concrete steps. Although explored more fully in Chapter 4, Robert Greenleaf’s (1977) servant leadership also highlights active engagement. The servant-leader does not wait passively; they act intentionally to serve, empower, and develop others. Far from being passive, servant leadership involves proactive steps to meet needs and foster growth. Across diverse theories — Adair’s action-centered model, Lewin’s styles, transformational leadership, and servant leadership — a common theme emerges: leadership requires action. Whether accomplishing tasks, building teams, inspiring vision, or serving others, leaders act to shape environments and move people forward.

These theoretical frameworks align with the biblical reality: leadership in God’s kingdom begins with the decision to follow and obey, which requires the leader to generate movement in some direction. Action is the point at which theory becomes practice, and conviction becomes leadership.

Ministry Application

For church and ministry leaders, the principle is clear: leadership begins when you choose to act. Waiting for the perfect conditions leads to paralysis. Ecclesiastes warns, “Whoever watches the wind will not plant; whoever looks at the clouds will not reap” (Eccl. 11:4). Leaders are called to move forward, trusting God with the results. Thus, the first principle of leadership is both accessible and demanding. Anyone can take action, yet not all will. Ministry leadership requires courage, faith, and willingness to embody the God who acts. Leadership begins when you choose to act. And when that action is taken in obedience to Christ, it has the power to change the world.

The Challenges

However, despite having a great vision, authentic motivation, and a clear desire to please the Lord, choosing to act as a leader is never without challenges. In fact, the action itself is often the crucible where leadership is tested. As such, leaders can expect that every choice creates the opportunity for unseen challenges. Scripture repeatedly reminds us that leaders are called not merely to see what should be done but to step forward in obedience and courage. The Bible is full of examples where leaders faced immense obstacles the moment they moved from intention to action. We will consider five challenges leaders can expect to face when they choose to act.

First, there is the challenge of risk and uncertainty. Every action carries consequences, some that readily present themselves and others that lurk in the shadows. When a leader chooses to act, he steps into a realm of uncertainty where the outcome is never fully guaranteed. A decision might fail, or it might succeed but at great cost; or the leader’s followers who were initially enthusiastic may begin to have apprehension about what is taking place. The reality of such uncertainty can create hesitation in the leader’s heart, but true leadership requires the courage to embrace it and move forward despite the unknown.

When Moses finally stood before Pharaoh to demand Israel’s release, he faced immense uncertainty (Exod. 5). Despite God’s command to confront Pharaoh, Moses did not know how Pharaoh would respond. And after confronting him, he could not have anticipated the events that followed. In addition, he had no clarity as to how Israel would respond to his leadership. Even if he could secure their release, would they follow? And then there was his hesitation because he didn’t believe he could succeed in the task (Exod. 4:10). Moses’ choice to act risked failure, humiliation, and even danger. Similarly, leaders today must recognize that every action involves stepping into the unknown. Faith-based leadership leans not on certainty but on trust in God’s sovereignty, acting in obedience even when the outcome is unclear (Heb. 11:8).

Second, there is the challenge of opposition. Action invites resistance. Once a choice is made and a direction is given, someone will object to that direction. To move in one direction is to reject other ways of accomplishing something, and though they agree with the larger vision, not everyone will agree with the path chosen to realize it. Leaders must expect opposition, even from good people. When a leader chooses a direction that others do not agree with, they will (not might) receive criticism, experience conflict, and, in worst-case scenarios, even be sabotaged. Sometimes the opposition is external, but often it arises within the team or organization. As such, leadership demands resilience in the face of pushback and the maturity to navigate dissent without abandoning the conviction to lead.

Moses not only faced stiff opposition from Pharaoh but also from within his own family. In Numbers 12, his brother and sister, Aaron and Miriam, criticized him for the woman he had married and challenged his unique role as God’s chosen leader. We read, “Then Miriam and Aaron spoke against Moses because of the Ethiopian woman whom he had married; for he had married an Ethiopian woman. 2 So they said, ‘Has the LORD indeed spoken only through Moses? Has He not spoken through us also?” (Exod. 12:1-2). Their opposition was rooted in jealousy and resentment. They thought they were just as qualified, if not more so, to lead God’s people. This demonstrates that leadership challenges often come not just from external enemies but also from those closest to us. For Moses, this opposition from family tested his humility and reliance on God, who ultimately vindicated him. An important clause at the end of verse two reads, “And the LORD heard it;” that is, He heard their complaint and was not pleased. However, leaders must remember that action always creates opposition because it disrupts the status quo and even stirs up envy. But the faithful leader responds not by shrinking back, but by praying, persevering, and focusing on God’s calling. In the moment, it is tempting to focus on the pushback and criticism, but that distraction can cripple the leader. Stay focused on the mission and entrust the criticism to the Lord.

Third, there is the challenge of taking responsibility.Choosing to act means accepting ownership of the results. This is one of the heaviest burdens of leadership. Inaction may protect a leader from blame or failure, but action exposes a leader to accountability. Leaders must be prepared to bear responsibility for both success and failure, often publicly and under scrutiny. When the apostle Paul acted on his calling to spread the gospel, he accepted responsibility for the churches he planted (2 Cor. 11:28). He bore the weight of their struggles, rebuked them when they strayed, and encouraged them when they faltered. Similarly, leaders today cannot act and then evade the personal responsibility that comes with leadership. Choosing to act means embracing accountability for both the successes and the failures that follow.

Fourth, there is the challenge of fatigue and the need for persistence.Leading and making decisions are not one-time events but repeated acts. Each decision to move forward requires energy, conviction, and perseverance. Leaders sometimes face mental exhaustion, sometimes called “decision fatigue,” during this process. This is the exhaustion that comes from the constant weight of responsibility. The challenge lies not only in acting once but in sustaining the will to act consistently over time. Elijah, after confronting the prophets of Baal on Mount Carmel, fell into despair and exhaustion (1 Kings 19:4). He fled from Jezebel after a great victory over her priests and false god, Baal. She responded by vowing to kill Elijah (v. 2). He was evidencing fatigue, so much so that God sent an angel to minister to him. Leadership is not a one-time event; it demands repeated courage and persistence. Leaders may experience fatigue, weariness, or discouragement, but the lesson of Elijah reminds us that God provides renewal for weary leaders when they rest in Him.

Fifth, there is the challenge of ethical complexity.Leadership is rarely a choice between obvious good and obvious evil, as in the case of Elijah and Jezebel. More often, it is a decision between competing goods or the “least bad” option. Ethical tension can paralyze leaders who fear making the wrong move. Yet leadership requires the courage to act even when the moral terrain is uneven, while anchoring decisions in integrity and principle. Daniel, serving under pagan kings, faced morally complex situations where his loyalty to God clashed with the demands of the empire. When he was first sent to Babylon, he was offered the “delicacies” of the king’s table (Daniel 1). He instead opted for a bland diet of vegetables and water. Later in life, a law was passed requiring all prayers to be made to Darius, the king, for a period of 30 days (Daniel 6). Who would have blamed him if he closed his curtains and prayed to the Lord in the privacy of his own home? His decision to act faithfully meant inviting the king’s wrath and facing the lions’ den. For modern leaders, ethical challenges rarely present clear-cut answers. Choosing to act requires anchoring decisions in God’s Word and character, trusting Him with the consequences.

Choosing to act as a leader is, therefore, both essential and costly. Inaction may seem safer, but it ultimately erodes trust and effectiveness. Taking action, however, involves risk, opposition, responsibility, fatigue, and ethical tension. Yet, as we see in the lives of the saints, effective leadership never comes from passive inaction. The biblical record reminds us that God calls leaders not merely to believe but to act in obedience, even at personal cost. Faithful leadership requires courage and sacrifice, trusting in the grace and sufficiency of Christ.

The Trap to Avoid

True leadership requires presence, engagement, and intentional action. Laissez-faire, however, is often mislabeled as a “style” of leadership when in reality it is the absence of leadership. The term is from the French and literally means “let’s do” or “let it be.” As a leadership approach, it proposes a hands-off management style in which leaders grant significant autonomy and freedom to team members, trusting them to make decisions and solve problems independently with minimal guidance. While it can initially look like a leader is empowering his people, in practice, it often manifests as neglect. Rather than fostering initiative, laissez-faire leaves followers without guidance, direction, or accountability. Let’s consider four problems associated with this “leadership” style.

First, it is an abdication of responsibility. Leadership, by its very nature, requires bearing the weight of responsibility. A laissez-faire leader, however, withdraws from this responsibility, leaving decisions, direction, and discipline entirely to others. This is not delegation, which involves empowering others within clear boundaries and shared accountability, but abdication, which abandons the leader’s role altogether.

Second, it is the absence of influence. John Maxwell defines leadership as “influence, nothing more, nothing less.” By contrast, laissez-faire leadership is the refusal to exercise influence. Without engagement, a leader forfeits the opportunity to shape outcomes, guide values, or protect their people. In this way, laissez-faire is not neutral; it actively damages group dynamics by removing the stabilizing presence of structured leadership.

Third, it tends towards organizational drift. John Adair’s Action-Centered Leadership emphasizes balancing task, team, and individual needs. Laissez-faire, however, undermines all three. Without task clarity, goals are neglected. Without team cohesion, conflict sets in. Without care for individuals, morale erodes. The result is organizational drift, where people work in isolation from one another and from the larger organization, and the mission suffers for lack of coordination.

Fourth, it fosters negative ethical consequences. Leadership carries a moral dimension. To neglect the needs of followers is an ethical failure. Proverbs warn that “where there is no vision, the people perish” (Proverbs 29:18). When leaders choose inaction, they abandon those entrusted to their care, exposing them to possible confusion, division, or exploitation. True leaders understand that the very act of leadership requires taking responsibility for those who follow them.

A biblical example of laissez-faire leadership is seen in Eli the priest (1 Samuel 2-3). Eli’s sons, Hophni and Phinehas, were corrupt priests who abused their position for personal gain and committed grievous sins against God and His people. Scripture tells us that Eli knew of their wickedness but failed to restrain them (1 Samuel 3:13). Though he occasionally rebuked them, he took no meaningful action to correct their behavior or remove them from leadership. Eli’s passivity exemplifies laissez-faire “leadership.” He allowed sin and disorder to flourish because he abdicated his responsibility to act. The consequences were devastating: Israel lost confidence in its priesthood, God’s judgment fell upon Eli’s household, and his family line was cut off from priestly service. Eli’s story is a sobering reminder that neglect is not neutrality. By failing to lead, he failed his people and dishonored God.

Laissez-faire is not a legitimate form of leadership but a counterfeit that cloaks passivity in the language of freedom. True leadership does not retreat from responsibility. It embraces the hard work of guiding, influencing, and serving others. Eli’s example shows that neglectful leadership not only undermines mission and morale but also invites divine judgment. To lead well, one must reject the temptation of inaction and instead step forward with clarity, courage, and conviction.

Reflection Questions

- Where in your life or ministry are you tempted to delay action while waiting for perfect conditions?

- Which biblical leader most challenges you as an example of faith in action?

- How might small, daily acts of obedience compound into long-term fruit in your ministry?

- How does your understanding of God as One who acts shape your own leadership decisions?

Suggested Readings

- Adair, John. Action-Centred Leadership. McGraw-Hill, 1973.

- Burns, James MacGregor. Leadership. Harper & Row, 1978.

- Greenleaf, Robert K. Servant Leadership. Paulist Press, 1977.

- Goleman, Daniel. Emotional Intelligence. Bantam, 1995.

- Lewin, Kurt, Ronald Lippitt, and Ralph K. White. Patterns of Aggressive Behavior in Experimentally Created “Social Climates”. Journal of Social Psychology, 1939.

- Maxwell, John C. The 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership. Thomas Nelson, 1998.

- Blackaby, Henry, and Richard Blackaby. Spiritual Leadership: Moving People on to God’s Agenda. B&H, 2001.